Declining grade of Gold – Are the cost disadvantages linear?

This is an analysis that I have been meaning to do for a while that simply looks at how mining a declining ore grade affects costs. This is a particularly important analysis for investors of gold stocks as my sense of the market is that the grades of gold being mined are declining faster than any other commodity, and additionally, replacement reserves for gold companies are grossly lower quality than reserves that are currently being mined.

The markets were awful while I was away on vacation, and some of the market fears from the subprime mortgage market spilled over into commodities. These fears as well as fears of stagflation or hyper-inflation are part of what is driving gold prices and gold stocks. The idea is that gold will hold wealth better than paper currency that is simply printed at will.

Figuring out what gold bullion is “worth” is very easy, just go to Kitco.com. If you think the price of gold will double, well, just buy the bullion and your investment will double.

Figuring out what a gold stock is “worth” is a very complicated thing and nothing about how a company is run is in your control. Proper evaluation of a gold stock requires an enormous amount of time. A simple linear extrapolation that if they double production they double earnings is proving to be false due to increases in costs that would be best described as a hyperinflation of costs, as in the Goldcorp 2004 project of costs for 2006 of $70/oz that ended up 179% higher at $195/oz. Gold stocks also have a propensity to issue equity at will, highly diluting wealth as well.

My suspicions are that gold producers are mining off their higher grades at a rate that leaves drastically reduced grades left to be mined and they have drastically lower grades in replacement properties so new mines do not have any chance of coming close to the profitability of historical mines despite higher gold prices.

The question I want to answer is how does the declining grade affect costs. I suspect that costs do not increase linearly with declining grade, but exponentially and if I am correct, many investors are going to find themselves in serious trouble with their gold stock investments, even if the price of gold doubles.

As the purpose of this investigation is to simply understand what happens to costs when all things are equal except the grade declining, I will make some very simple assumptions. First, assume there is a part of the processing linked to the cost of grinding the ore and extracting the gold. For this analysis assume the cost is fixed per ton of ore. I will assume a cost of $25/ton of ore, as you might have for an open pit operation. At the end of this will be a gold concentrate that requires more processing to extract the pure gold. The second part of the process assumes a fixed cost per ounce of gold. I will assume a fixed cost of $10/oz of gold.

Further, I will look at how a 0.5 g/ton decline affects costs from 100 g/ton down to 1 g/ton. The last assumption will be that 32 grams of gold must be extracted to get one ounce of gold. Recovery is never 100% and using this number works out to 97% recovery. My educated guess as a chemist is that the overall percent recovery would also decline with declining grade, so more than likely this analysis will understate the increasing costs with grade.

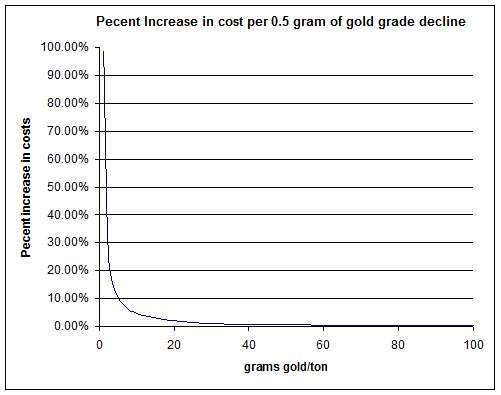

I set up a simple spread sheet at http://spreadsheets.google.com/pub?key=pHy7hQjBLOcqL73eztsvRaQ. It shows that with the costs used a half-gram decline in grade when the grade is over 30g/ton is utterly marginal to costs. The follow graph is the percent increase in cost as the grade increases.

This graph demonstrates beyond my wildest expectations that costs hyper-inflate for low grades of ore. The prices I used would be for a low cost open pit operation. The graph does not explain how Goldcorp’s projected costs ended up being 179% higher over a two-year period.

When I put a cost of $175/ton of ore for processing for underground mining my model gives costs of $80/oz when the grade is 79.5g/ton, reasonably close to Goldcorp’s $80/oz when they were mining a grade of 77g/ton. At 30g/ton the model gives a cost of $187/oz, very close to the $195/oz they had around that grade. Interestingly, the model shows that it would cost $5,600/oz to mine underground grades of 1g/ton, and double that, $11,200, for a grade 0.5g/ton.

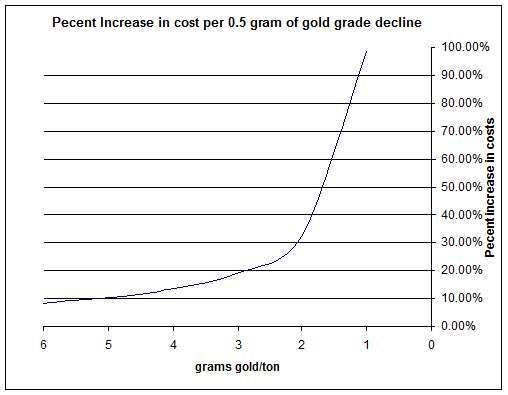

This is a very simple model, but the lesson it shows is something that every gold investor ought to understand. Below is the graph reproduced for grades 6 grams and less, showing the increased percentage cost for a grade decline of 0.5g/ton, and I reversed the director of the x-axis so you can see the out of control, concave up, shape of the curve.

This graph should have investors of companies with low-grade reserves feeling utterly ill. I would suggest that what it means is that anyone signing their name saying that a low-grade reserve is economically viable is either incompetent, unethical or they think investors are truly gullible and stupid.

I have worked as a chemist in a lab and the entire economic viability of the feasibility study rests on the accuracy and extrapolation of the assay results. The lab I worked in we used to regularly send out samples to other labs as a crosscheck on our results and there would typically be up to a 30% variation in results. To test where the problem in results lay, I sent out duplicate samples labelled differently and carefully prepared and tested standards and the results returned were out by 30%.

This graph is showing that when grade declines from 6g/ton to 5.5g/ton, costs increase by almost 10%. A half-gram decline at 3g/ton has cost increases of about 20%. At 2g/ton the same decline results in a 30% increase in costs, and at 1g/ton the decline results in about a 100% increase in costs. When you consider the potential error in assay results, the margin of error in these feasibility studies on low-grade deposits is potentially so enormous; these kinds of investments simply are not investments, but truly a form of gambling.

Conclusion:

The cost increases in low-grade deposits are not linear, but exponential and imitate a hyperinflation of costs as grade declines. In high-grade deposits errors in feasibility studies due to errors in grade or small declines in grade are relatively small and have a minor effect on investment decisions. Feasibility studies on low-grade deposits are highly suspected for huge errors due to the grossly different economics of low-grade deposits from small errors in assumptions and data. Using these studies for investment decisions resembles gambling more than investing.

2 comments :

Hi Deborah,

A great post as usual. I follow your logic and points I think. Here's what I'm wondering:

You know, all-too-well, how much poor and subjective information there is in this industry segment. I have read elsewhere, from other analysts of Precious Metals mining stocks, that they observe that some of the miners have been focusing their current extraction efforts on lower grade deposits given the higher prices for the metals in the past couple years. Purportedly, 'saving higher grade deposits for a rainy-day' or something like that. But, I admit that I don't think I have ever read this description in the context of any specific miners where I could then dig-in and attempt to CONFIRM such statements. Yes, that lack of specificity alone makes one suspicious doesn't it?!

But I'm wondering if you have uncovered such specifics--illustrating EITHER of the two scenarios--regarding any of the miners lately?

Thanks for all your great work!

Mark

I have seen the mine lower grade stuff, but I figured that was because sometime they simply have to mine lower grade stuff to get to the better stuff.

They plan when they do this and if you read the management analysis it will often mention if they have a lower grade to mine and when they expect to get through it.

They also sometimes have less pure grades and sometimes mine in a way that they can still meet specifications, but get a better price for something with some bad impurities.

Post a Comment